I have a great fondness for Eric Rohmer's films whose verbosity and intellectuality I count as pluses in addition to their psychological and erotic tension. Here are his obits in The Guardian and NYTimes:

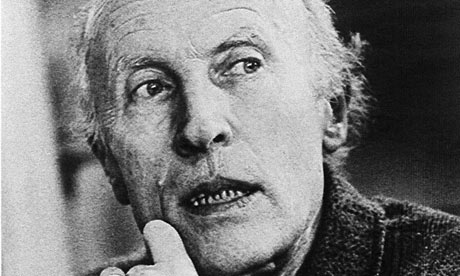

Eric Rohmer in 1985 Photograph: EPA

In Arthur Penn's intelligently unconventional private eye thriller Night Moves (1975), Gene Hackman's hero – who finds the mystery he faces as unfathomable as his personal relationships – is asked by his wife whether he wants to go to an Eric Rohmer movie. "I don't think so," he says. "I saw a Rohmer film once. It was kind of like watching paint dry."

Behind that exchange lies a jab at Hollywood's mistrust of any film-maker, especially a French one, who neglects plot and action in favour of cerebral exploration, metaphysical conceit and moral nuance. The Dream Factory, after all, had proved through trial and error that cinema is cinema, literature is literature, and the twain shall meet only provided the images rule, not the words.

Of the major American film-makers, perhaps only Joseph Mankiewicz allowed his scripts, fuelled by his own sparkling dialogue, to wag the tail of his movies. While acknowledging the brilliance, Hollywood punditry never failed to complain that Mankiewicz characters simply talked too much.

Rohmer, who has died aged 89, pushed even further into this disputed territory. The oldest of the group of critics associated with the film review Cahiers du Cinéma, who launched the French new wave in the late 1950s, Rohmer had (writing initially under his real name of Maurice Schérer) established impeccable credentials for a future film-maker. Among the objects of his admiration were Dashiell Hammett, Alfred Hitchcock (about whom he wrote a monograph with Claude Chabrol), Howard Hawks, and above all FW Murnau, the great visual stylist of the German expressionist era (on whose version of Faust he published a doctoral thesis). As a film-maker, however, he turned instead to such literary-philosophical luminaries as Blaise Pascal, Denis Diderot, Choderlos de Laclos and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

His first feature, Le Signe du Lion (The Sign of Leo), completed in 1959 after one false start and a handful of shorts, fitted comfortably into the early new wave formula of Parisian life, with its tale of a student musician, tempted into debt by a promised inheritance, who lapses into abject destitution after the legacy turns out to be a hoax. In retrospect, one can clearly see in it the seeds of Rohmer's later work. Showing little interest in plot or action, Rohmer concentrates on demonstrating how Paris itself becomes an objective correlative to the hero's state of mind, gradually metamorphosing from a welcoming city into a bleak stone desert as he realises that the friends from whom he might hope to borrow are all away for the vacation.

With Le Signe du Lion failing at the box office, Rohmer retreated into television where, while working on educational documentaries, he hatched his daring conception for a series of Six Moral Tales. Variations on a theme, each film would deal with "a man meeting a woman at the very moment when he is about to commit himself to someone else". Furthermore, as Rohmer later observed, the films would deal "less with what people do than with what is going on in their minds while they are doing it".

Made for TV, the first two films in the cycle, La Boulangère de Monceau (The Baker of Monceau, 1962) and La Carrière de Susanne (Suzanne's Career, 1963), shot in black and white and running for 26 and 60 minutes respectively, were too cramped in every respect to be more than clumsy foretastes of what was to come.

Completing the series for the cinema with La Collectionneuse (The Collector, 1966), Ma Nuit Chez Maud (My Night With Maud, 1969), his international breakthrough Le Genou de Claire (Claire's Knee, 1970) and L'Amour l'Après-midi (Love in the Afternoon, 1972), Rohmer found exactly what he needed in the bigger screens, longer running times, more expansive locations and availability of colour (actually in black and white, My Night With Maud uses the snowy landscapes of Clermont-Ferrand as a perfect counterpoint to its chilly Pascalian thematic). Backed by the richly sensuous role now played by the visuals, the somewhat arid intellectual dandyism of the first two films flowered into a teasingly metaphysical exploration of human foibles.

Le Genou de Claire, for instance, perhaps the most accomplished of the six films, is about a French diplomat, on the brink of both middle age and marriage, enjoying a brief lakeside vacation in Switzerland. Seduced by his idyllic summery surroundings, he begins casting an appreciative eye over the young women on show. Innocent dalliance, he assures himself, proclaiming that his courtly fancy has been captured by the perfection of the eponymous heroine's knee. Deeper down, though, as he comes to realise when a pert and pretty teenager responds to his casual flirtation by remarking on his resemblance to her father, lies a less palatable truth: there, but for the grace of God, goes a dirty old man.

Rohmer followed his Six Moral Tales with two similar cycles, identical in style, method and accomplishment. First came Comedies and Proverbs: La Femme de l'Aviateur (The Aviator's Wife, 1980), Le Beau Mariage (A Good Marriage, 1981), Pauline à la Plage (Pauline at the Beach, 1982), Les Nuits de la Pleine Lune (Full Moon in Paris, 1984), Le Rayon Vert (The Green Ray, 1986) and L'Ami de Mon Amie (My Girlfriend's Boyfriend, 1987). Then, Tales of the Poor Seasons: Conte de Printemps (A Tale of Springtime, 1989), Conte d'Hiver (A Winter's Tale, 1992), Conte d'Eté (A Summer's Tale, 1996) and Conte d'Automne (An Autumn Tale, 1998).

In between times, Rohmer also made a number of non-series films, most notably two literary adaptations which are rather different in their visual approach. Die Marquise von O... (The Marquise of O, 1976) adopts a severe neo-classical style in transposing Heinrich von Kleist's teasing early-19th-century novella about the social furore occasioned when a chaste young widow suffers a pregnancy which she insists can only be the result of an immaculate conception. Perceval le Gallois (1978), on the other hand, toys joyously with cut-out sets and false perspectives to invest his adaptation of Chrétien de Troyes's 12th-century Arthurian tale with the faux-naif aspects of an illuminated manuscript.

Both remain entirely consistent with the body of Rohmer's work, a highly original and endlessly fascinating attempt to render the interior exterior by mapping out the maze of misdirections that bedevil communications between the human heart and mind.

Rohmer guarded his private life fiercely – giving different versions of his date of birth and real name on different occasions, so that it is difficult to be certain of the truth. He was married in 1957 to Thérèse Barbet, and they had two sons.

Ronald Bergan writes: The Lady and the Duke (L'Anglaise et le Duc, 2001), set during the French Revolution, is as elegant as the heroine, a patrician Englishwoman who defies the citizens' committees. Always experimenting with visual style to suit the subject, Rohmer had the actors seen against artificial tableaux of Paris circa 1792. However, these are not painted backdrops, but perspective drawings, which are intriguingly digitally combined with the action. It proved that Rohmer at 81 was willing to utilise new technology.

Rohmer's last film, The Romance of Astrea and Celadon (Les Amours d'Astrée et de Céladon, 2007) revealed him as interested in the combination of the intellectual with the sensual among young people. Rohmer's achievement is in recreating fifth century Gaul, with shepherds, shepherdesses, druids and nymphs, and making it meaningful to a modern audience. If Rohmer's contemporary films evoked 18th-century novels and plays, his period pieces echoed present-day sexual relationships. Rohmer's characters are largely defined by their relationships with the opposite sex which take place in sumptuous hedonistic settings. For films that deal to a large extent with the resistence to temptation, they are tantalizingly erotic.

• Eric Rohmer (Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer), film director, born 21 March 1920; died 11 January 2010

• Tom Milne died in 2005

Eric Rohmer, the French critic and filmmaker who was one of the founding figures of the internationally influential movement that became known as the French New Wave, and the director of more than 50 films for theaters and television, including the Oscar-nominated “My Night at Maud’s” (1969), died on Monday. He was 89.

Skip to next paragraphMultimedia

Related

Times Topics: Eric Rohmer

Filmography: Eric Rohmer Profile Article: Eric Rohmer (February 11, 2001)

Post a Comment on ArtsBeat

Blogs

Go to Awards SeasonHis producer, Margaret Menegoz, announced his death in Paris, Agence France-Press reported. Relatives said he had been hospitalized a week ago but gave no further details about his condition, the news agency said.

Aesthetically, Mr. Rohmer was perhaps the most conservative member of the group of aggressive young critics who purveyed their writings for publications like Arts and Les Cahiers du Cinéma into careers as filmmakers beginning in the late 1950s. A former novelist and teacher of French and German literature, Mr. Rohmer emphasized the spoken and written word in his films at a time when tastes — thanks in no small part to his own pioneering writing on Alfred Hitchcock and Howard Hawks — had begun to shift from literary adaptations to genre films grounded in strong visual styles.

His most famous film in America remains “My Night at Maud’s,” a 1969 black-and-white feature set in the grim industrial city of Clermont-Ferrand. It tells the story of a shy, young engineer (Jean-Louis Trintignant) who passes a snow-bound evening in the home of an attractive, free-thinking divorcée (Françoise Fabian).

The conversation, filmed by Mr. Rohmer in a series of carefully but unobtrusively composed long takes, covers philosophy, religion and morality, and while the flow of words at times takes on a distinctly seductive subtext, the encounter ends without a physical consummation. But a bond is formed between the two characters that movingly re-emerges five years later, when they meet again in the brief postscript that closes the film.

“My Night at Maud’s” was the third title in his “Six Moral Tales,” a series of films that Mr. Rohmer began in 1963, though for economic reasons it was the fourth to be filmed. In each of the six films, a man who is married or engaged finds himself tempted to stray but is ultimately able to resist. His films are as much about what does not happen between his characters as what does, a tendency that enchanted critics as often as it drove audience members to distraction.

“I saw a Rohmer movie once,” observes the Gene Hackman character in Arthur Penn’s “Night Moves” (1975). “It was kind of like watching paint dry.”

In his private life, Mr. Rohmer was reclusive if not secretive. “Eric Rohmer” was, in fact, a pseudonym, one of several that he experimented with early in his career. According to “Who’s Who in France,” he was born Maurice Henri Joseph Schérer in Tulle, a city in southwestern France, on March 21, 1920; other sources give his birth name as Jean-Marie Maurice Schérer and place his origins in the northeastern city of Nancy.

After publishing the novel “Elisabeth” under the name Gilbert Cordier, he moved to Paris in 1950, where he began frequenting the ciné-clubs of the Latin Quarter, making the acquaintance of four other young cinephiles with whom his career would remain intertwined: Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Claude Chabrol and Jacques Rivette. With Mr. Rivette, he founded a short-lived film magazine, La Revue du Cinéma, but when that initiative collapsed after five issues, he joined the reviewing staff of Les Cahiers du Cinéma, a publication that acquired a fashionable notoriety for the violently iconoclastic reviews of the young Truffaut.

In 1952, Mr. Rohmer made his first attempt to direct a feature film, to be titled “Les Petites Filles Modèles,” but the project was abandoned when its producer declared bankruptcy. No footage is known to exist. Not until his Cahiers colleagues began to enjoy a measure of success as filmmakers — the term La Nouvelle Vague (The New Wave) was coined by a journalist for L’Express in 1957 — was Mr. Rohmer able to mount another long form production. But “Le Signe du Lion” (1959), a moody tale of an American expatriate who finds himself down and out in Paris, did not capture the public imagination the way Truffaut’s “400 Blows” and Godard’s “Breathless” did, and Mr. Rohmer returned to editing Les Cahiers, a job he held until 1963.

Mr. Rohmer’s real breakthrough came in 1962 with the 26-minute short “La Boulangère de Monceau” (“The Bakery Girl of Monceau”). Filmed in 16-millimeter black and white, it was the first of the “Six Moral Tales,” based on fictional sketches he had written, he later said, long before he dreamed of becoming a filmmaker.

After a second short film, “La Carrière de Suzanne” (1963), Mr. Rohmer returned to the feature length format with “La Collectionneuse” (1967), the fourth episode of the series but the third to be filmed. The story of a young woman (Haydée Politoff) who systematically collects lovers, the film won the Silver Bear at the Berlin Film Festival and restored Mr. Rohmer’s place in the front rank of the New Wave. The series continued with three more features: “My Night at Maud’s,” “Claire’s Knee” (1970) and “Love in the Afternoon” (1972).

After experimenting with two stylized period films, “The Marquise of O ...” (1976) and “Percival le Gallois” (1978), Mr. Rohmer initiated a new series, “Comedies and Proverbs,” with the 1981 “La Femme de l’aviateur.” The six films in this group were illustrated traditional sayings or quotes from celebrated authors (from La Fontaine to Rimbaud), and were largely built around the flirtations and fickle emotions of young people, and incorporated, notably in “Le Rayon Vert” (1986), a new element of improvisation.

Mr. Rohmer undertook a final series, “Tales of the Four Seasons,” with “Conte de Printemps” in 1990, this time providing a philosophical love story for each season of the year. The series ended with the exquisite “Conte d’Automne” in 1998, in which Mr. Rohmer moved beyond his focus on youth to tell a movingly autumnal story of a widow (Béatrice Romand) with a teenage son who finds love in an unexpected place.

Mr. Rohmer’s late career found him moving happily among small projects for television (including “L’Arbre, le Maire et la Médiathèque,” 1993), an early experiment with digital technology (“The Lady and the Duke,” 2001), and a true-life spy story (“Triple Agent,” 2004). His final theatrical film was the 2007 “Astrée and Céladon,” a retelling of a 17th-century love story with magical overtones, filmed in a self-consciously academic style that suggested the paintings of Poussin and Fragonard.

He is survived by a younger brother, the philosopher René Schérer, and by a son, the journalist René Monzat.

In opposition both to the intensely personal, confessional tone of much of the work of Truffaut and the politically provocative films of Godard, Mr. Rohmer remained true to a restrained, rationalist aesthetic, close to the principles of the 18th-century thinkers whose words he frequently cited in his movies. And yet Mr. Rohmer’s work was warmed by an undercurrent of romanticism and erotic yearning, made perhaps all the more affecting for never quite breaking through the surface of his elegant, orderly films.

No comments:

Post a Comment