"On the surface the new novel is about feminism and the right of women to choose not to bear children. But an underlying theme is whether liberal nationalism is an oxymoron, whether the rights of the individual (the essence of liberalism) can be reconciled with the needs of the nation." -- from my New York Journal of Books review of The Extra by Abraham B. Yehoshua. For an excerpt from the novel see my addendum to that review below.

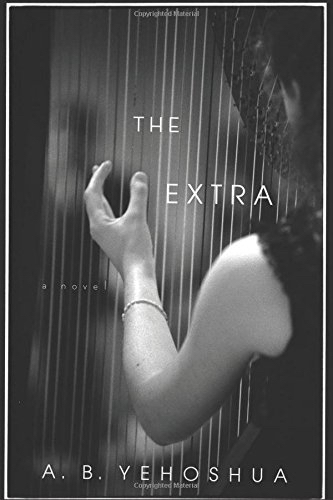

The essential objective of nationalism is to ensure that a particular people with a common past will enjoy a common future. The decision by a citizen of a country founded by a nationalist movement not to have children would appear to contradict that national objective. This conflict between individual rights and the needs of the nation is central to The Extra, Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua’s newest novel to appear in English translation, which is published today by Boston and New York publisher Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

The essential objective of nationalism is to ensure that a particular people with a common past will enjoy a common future. The decision by a citizen of a country founded by a nationalist movement not to have children would appear to contradict that national objective. This conflict between individual rights and the needs of the nation is central to The Extra, Israeli novelist A.B. Yehoshua’s newest novel to appear in English translation, which is published today by Boston and New York publisher Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

In my New York Journal of Books review of The Extra I write,

“On the surface the new novel is about feminism and the right of women to choose not to bear children. But an underlying theme is whether liberal nationalism is an oxymoron, whether the rights of the individual (the essence of liberalism) can be reconciled with the needs of the nation.”

Noga is a 41 soon to be 42 year-old divorced child-free by choice Israeli harpist who lives in Holland where she plays in a regional orchestra. She takes a three month leave of absence from the orchestra to house-sit her elderly mother’s apartment during the latter’s trial residence in an assisted living facility. Her brother Honi, a film and television producer, gets her jobs appearing as an extra in movies, commercials, and an opera performance.

Yehoshua deploys a plot device to arrange for Noga to meet and converse with her former husband Uriah who left her a decade ago when she announced she did not want children and has since remarried and fathered two children with his new wife. Notwithstanding his new family, Uriah is still not at peace with Noga’s choice to be child-free. He tells her,

“‘… Anyway, if even in the beginning you had your doubts about having children, I, as a young man, swept away by love, might have interpreted your hesitation as a teenager’s fleeting radical protest against the state or against the world.’

“‘The state?’

“‘In the hackneyed sense that if Israel is going downhill, better not to have children here.’

“‘I never said that and never thought that. And even if I was sometimes too radical for your taste, I could have given birth to radical children who would aid and abet my radicalism.’

“‘In other words, the future here is not secure, is full of danger.’

“‘No.’ She raises her voice. ‘Who am I to presume to know what will be here in the future? Who am I to decide if the danger is real or only exists in newspaper articles? My parents conceived me during a terrible, shocking war, and still the two of them didn’t presume to know. Oy, Uriah, you won’t get free of a disobedient love if you keep rehashing old stuff.’”

Nonetheless, they continue to rehash the old disagreement that led to their divorce. To add insult to injury Noga’s mother takes Uriah’s side, and her brother Honi helped Uriah get in touch with Noga. Readers can well imagine the relief with which Noga returns to Holland, her orchestra and the work she loves.

I conclude my NYJB review by praising Stuart Schoffman’s translation and Yehoshua’s prose: “Four and a half decades after his first book’s publication his 20th shows Yehoshua’s writing chops are undiminished and his content fearlessly topical.” See that review for a fuller discussion of the novel.