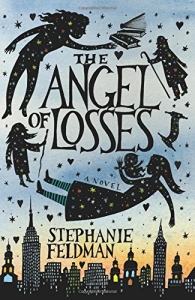

"Stephanie Feldman’s debut novel The Angel of Losses, which was published last week by New York-based HarperCollins imprint Ecco Press, is a welcome addition to the Jewish fantasy fiction genre." --examiner.com

"Stephanie Feldman’s debut novel The Angel of Losses, which was published last week by New York-based HarperCollins imprint Ecco Press, is a welcome addition to the Jewish fantasy fiction genre." --examiner.com

In my New York Journal of Books review of the novel I write, “The Angel of Losses is recommended to nerdy (in the best sense of the word) secular Jewish and philo-Semitic readers whose genre interests include the confluence of contemporary and fantasy fiction.” Read that review first. Additional remarks that appeared in a different and now defunct publication begin with the next paragraph.

Jewish books: Stephanie Feldman's The Angel of Losses is an auspicious debut

Stephanie Feldman’s debut novel The Angel of Losses, which was published last week by New York-based HarperCollins imprint Ecco Press, is a welcome addition to the Jewish fantasy fiction genre. In my New York Journal of Books review of the novel I write, “The Angel of Losses is recommended to nerdy (in the best sense of the word) secular Jewish and philo-Semitic readers whose genre interests include the confluence of contemporary and fantasy fiction.”

The novel might also appeal to the growing number of gentiles who, like its protagonist Marjorie Burke, discover they have Jewish ancestry, as well as to those who always knew that a parent or grandparent is Jewish. In my NYJB review I cite the case of former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright who learned at age 60 that her parents were Jewish apostates. Current Secretary of State John Kerry, on the other hand, has always known that his paternal grandparents were born Jewish. In my own family some of my paternal great-uncles married Protestants and raised their children in their mother’s faith. But one of my dad’s Protestant first cousins was fascinated by her Jewish father’s religious heritage, converted to Judaism, and married a rabbi.

In The Angel of Losses Marjorie’s sister Holly converts to Judaism without knowing about her grandfather’s ancestry. What tips Marjorie off that her late grandfather might have been Jewish are stories he wrote about a character he called The White Rebbe. The stories also draw the attention of her brother-in-law Nathan who is a member of a mystical Jewish sect called The Berukhim Penitents who are mentioned in the stories.

Feldman does not refer to the Berukhim Penitents as Hasidic, and even dates the sect’s founding to the Sixteenth Century thus predating Hasidism which started in the Eighteenth Century, but the Hasidim are the only sects who call their rabbis rebbe. Moreover the Berukhim Penitents are so preoccupied with the coming of the messiah that when their rabbinic leader died centuries ago no successor was chosen, and instead they await their deceased rabbi’s return.

This sounds a lot like the Bratslav (or Breslov) Hasidim who have remained devoted to their story telling rebbe Nachman since his death in 1810 and have never chosen a successor, and instead await Nachman’s return as the messiah. Chabad Lubovitch is another messianic Hasidic sect that has not chosen a successor since it’s seventh rebbe’s death in 1994 and likewise awaits his messianic return. Feldman’s fictional Berukhim Penitents combine aspects of both sects, and like the Lubovitch Hasidim were originally based in Lithuania, whereas the Bratslav Hasidim were from the Ukraine. In his doctoral dissertation Conservative Rabbi David Siff points out that the two sects that don't have a living rebbe are the most messianic of all the Hasidic sects.

One detail that seemed odd to me was when Feldman referred to Lithuanian Orthodox synagogues as temples. Reform Judaism often refers to its houses of worship as temples, but that appellation is rarely used among the Orthodox. But that is a minor quibble that is easy to overlook in this entertaining and enjoyable read. For a fuller discussion of the novel read my NYJB review.

Stephanie Feldman

Stephanie Feldman