Loneliness is defined as perceived social isolation, and it's not based on the number of people around you.

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Study: Loneliness spreads more quickly among friends than family

- Like happiness, loneliness can spread out three degrees of separation

- Loneliness spreads much more easily among women than among men

(CNN) -- Have you ever felt cut off from other people, even if there are plenty around you? Maybe you felt all alone in the world, but you were making other people feel lonely without even realizing it.

New research suggests loneliness can actually travel from person to person, spreading up to three degrees of separation. That means if your neighbor's cousin's friend is lonely, you may have a good chance of being lonely, too.

The results, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, were also mentioned in the recent book "Connected" by Dr. Nicholas Christakis at Harvard University and James Fowler at the University of California, San Diego. The book explores how happiness, obesity, smoking and a slew of other behaviors and habits are contagious among groups of people who know one another.

Read more about the book

John Cacioppo, a psychologist at the University of Chicago who has written a book called "Loneliness," teamed up with Christakis and Fowler to study the effect of this phenomenon in social networks.

The authors focused on data from the Framingham Heart Study, which has followed thousands of people in Framingham, Massachusetts, since 1948. The loneliness research looked at the second generation in the study, which includes 5,124 people.

In the heart study, researchers kept in touch with participants every two to four years, asking them about depression, loneliness and other issues. They also kept a record of their friends. This allowed Christakis, Fowler and Cacioppo to look at the subjects' social networks over time.

If a direct connection in your social network is lonely, you are 52 percent more likely to be lonely, the researchers found. At two degrees of separation -- a friend of a friend -- it's 25 percent. At three degrees, someone who knows your friend's friend, it's 15 percent.

By helping lonely people on the periphery of a social network, "We can create a protective barrier against loneliness that will keep the whole network from unraveling," Christakis and Fowler wrote in "Connected."

The results are surprising because "we think of loneliness as something that affects a person who is by himself or herself," Ed Diener, professor of psychology at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, said in an e-mail. He was not involved in the study.

But it makes sense that the way a lonely person behaves could influence others, and those people could respond in kind to more friends, social scientists say.

"If lonely people act out behaviors that alienate others, some others will learn to enact those same behaviors, sometimes in reaction against the lonely person," Diener said.

Loneliness is defined as perceived social isolation, and it's not based on the number of people around you, Cacioppo said. Evolutionarily, it was important for early humans to know how many peers they could count on, work with and survive with, as well as who would betray them, he said.

"That's why the quality, not the quantity, of relationships is what's related to whether someone feels isolated or feels satisfied with their relationships," he said.

Cacioppo's earlier research says people have different baseline levels of loneliness, meaning some people have a greater need than others for social connection. From that perspective, it follows that someone who is highly sensitive to disconnection would more strongly promote lonely feelings in the network, he said.

Both lonely and nonlonely people prefer nonlonely people, and sometimes the lonely are even harsher to others who feel disconnected than the nonlonely people. This helps leave the lonely people with fewer friends, Cacioppo said.

In the social network study, mood did not affect how loneliness was transmitted, he said. Participants were asked how depressed they were, and this did not seem to affect whether they passed loneliness along the network.

The study also found that loneliness spreads much more easily among women than among men, citing the idea that women may be more likely to express and share emotions, as well as the observation that there may be greater stigma associated with loneliness among men. Happiness, by contrast, does not seem to have gender distinctions in the way it spreads, according to Christakis and Fowler's research.

People who are lonely may be motivated to seek social connection, increasing the likelihood that others around that person will be exposed to loneliness, the authors said.

Loneliness spreads more quickly among friends than family, but this finding may be limited to older people, as the average age in the sample was 64 years old, the authors said. Cacioppo, though, said the pattern generally makes sense because the cost of leaving a friendship is less than cutting off a family member, so people are more likely to isolate themselves from friends than close relatives or spouses.

Although these effects are stronger in person, they also have implications for online social interactions, he said.

"If you have an important friend and they are really grumpy and say nasty things on email, you may walk into the next room and be grumpy to someone else," he said.

The findings have implications for communities, Cacioppo said. City planners and policymakers should consider interventions such as sidewalks that allow neighborhood residents to interact more in public spaces, so that if someone is feeling down, others can help bring that person out of it.

In terms of therapy, it's important for lonely people to understand the condition and what it does to the brain, he said. Those who are lonely tend to view things as more threatening, and if they understand that, they can help themselves temper such strong reactions.

"We can correct our tendency to want to act grumpy to others," he said.

Diener said the research is important, building off of the "Connected" authors' earlier work on social networks.

"This series of studies shows us that we don't just live in individual worlds, but are influenced often in unconscious ways of which we are not aware," he said.

479 shares | 163 comments

-->

Share this on:

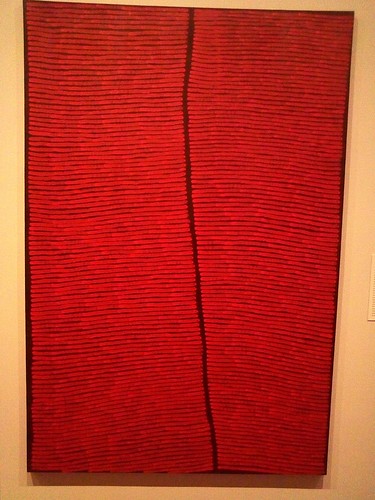

"Awelye, Bush Melon, and Bush Melon Seed Dreamings" by Minnie Pwerle

"Awelye, Bush Melon, and Bush Melon Seed Dreamings" by Minnie Pwerle "Yarla Yam Dreaming" by Lorna Fencer Napurrula

"Yarla Yam Dreaming" by Lorna Fencer Napurrula "Bush Fire Dreaming" by Ronnie Tjampitjinpa

"Bush Fire Dreaming" by Ronnie Tjampitjinpa

"Winpa" by Daniel Walbidi

"Winpa" by Daniel Walbidi

Jews traditionally use the Hebrew word tsedakah which means righteousness (and implies an obligation) rather than the English word charity (which connotes optional) to refer to helping the less fortunate. The tax code provides incentives to donate, but there are only five days left to make 2009 charitable donations. If you have been waiting until the last moment to chose which Jewish organizations to support take a look at the list in the right hand margin under the heading Recommended Jewish Charities. I first mentioned several of these almost eight weeks ago

Jews traditionally use the Hebrew word tsedakah which means righteousness (and implies an obligation) rather than the English word charity (which connotes optional) to refer to helping the less fortunate. The tax code provides incentives to donate, but there are only five days left to make 2009 charitable donations. If you have been waiting until the last moment to chose which Jewish organizations to support take a look at the list in the right hand margin under the heading Recommended Jewish Charities. I first mentioned several of these almost eight weeks ago