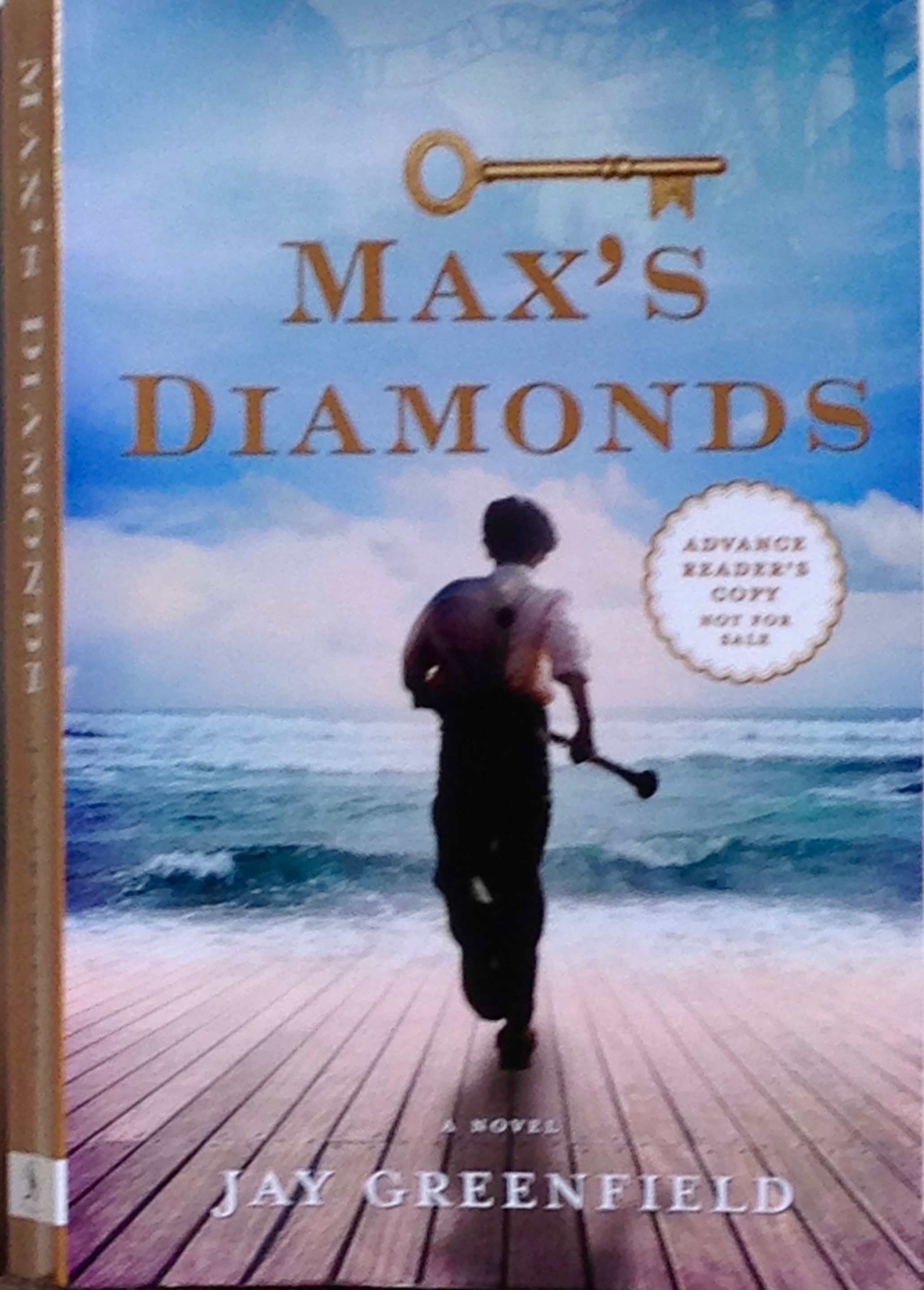

"Max’s Diamonds, Jay Greenfield’s debut novel published last week by New York publisher Chickadee Prince Books, is a guilty pleasure, a book I enjoyed and could barely put down for its suspenseful serpentine plot despite its pedestrian and occasionally heavy-handed prose." -- From my examiner article (which begins in the next paragraph). Also see my New York Journal of Books review, which concludes "with Max's Diamonds readers are rewarded with a fun and absorbing read whose fortuitous May publication date makes it a felicitous beach or airplane book."

"Max’s Diamonds, Jay Greenfield’s debut novel published last week by New York publisher Chickadee Prince Books, is a guilty pleasure, a book I enjoyed and could barely put down for its suspenseful serpentine plot despite its pedestrian and occasionally heavy-handed prose." -- From my examiner article (which begins in the next paragraph). Also see my New York Journal of Books review, which concludes "with Max's Diamonds readers are rewarded with a fun and absorbing read whose fortuitous May publication date makes it a felicitous beach or airplane book."

Max’s Diamonds, Jay Greenfield’s debut novel published last week by New York publisher Chickadee Prince Books, is a guilty pleasure, a book I enjoyed and could barely put down for its suspenseful serpentine plot despite its pedestrian and occasionally heavy-handed prose. Like Greenfield, the novel’s protagonist Paul Hartman grows up in a Jewish community in Rockaway, Queens and goes on to become a successful lawyer. Greenfield is old enough that like Paul he probably encountered anti-Semitic colleagues early in his legal career. To Greenfield’s credit he makes complex legal cases understandable to the general reader.

But this is a work of fiction, not a memoir, and some of the fictional character’s biographical details differ from those of the author. The eponymous diamonds, which fund Paul’s education, are of unethical provenance, and come with obligations that threaten to impede Paul’s professional advancement. In my New York Journal of Books review of the novel I compare Paul’s predicament trying to balance the irreconcilable demands of his professional ethics and his unethical relatives to that of the young Michael Corleone in The Godfather movies.

According to a mutual friend another difference between the author and his character is that Greenfield’s parents and grandparents were Eastern European Jews whose mother tongue was Yiddish, while Paul’s parents were German speaking Jews from a majority German speaking part of northwestern Bohemia who adopted Yiddish as adults to avoid speaking the language of the Nazis. The elder Hartmans’ decision to switch from German to Yiddish strikes me as implausible and ahistorical.

Historically inaccurate details are distracting to knowledgable readers. We read historical fiction to take our imaginations to another time and place, but when the details don’t fit that time and place the effect is spoiled.

Czech Jews switched from Yiddish to German in the 19th Century, Twentieth Century Bohemian and Moravian Jews were bilingual in German and Czech, Yiddish was no longer spoken, and early 20th Century Jewish writers wrote in German. How would people who did not grow up speaking Yiddish and were never immersed in a Yiddish speaking community suddenly know Yiddish?

Paul’s parents might have learned Yiddish from their Eastern European grocery store customers and fellow Orthodox synagogue congregants and/or taken Yiddish classes offered at The Workman’s Circle, YIVO, or local colleges, and his survivor relatives who arrive after the war might have learned it from other inmates in concentration camps and post-war displaced persons camps, but the narrative doesn’t spell out these details other than to say, “that although German, more than Yiddish, had been his parents’ principal language in Europe, they refused to speak it in America.”

But if the language switch is historically unlikely, it may nonetheless be emotionally accurate. When I recall the strong Jewish identities and sensitivity to anti-Semitism of Holocaust survivors in my acquaintance, the emotional tone of such a plot element seems right even though that specific detail is probably factually false.

I close my NYJB review emphasizing the positive, noting “Max’s Diamonds readers are rewarded with a fun and absorbing read whose fortuitous May publication date makes it a felicitous beach or airplane book.”

My poetry book Glued To The Sky is now also

My poetry book Glued To The Sky is now also