“The Hilltop is recommended to all readers who enjoy a good story grounded in current events.” -- from my New York Journal of Books review. Also see my examiner article, which begins with the next paragraph.

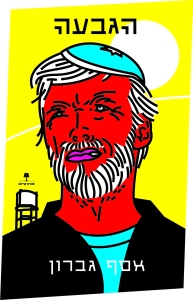

Israeli books: Assaf Gavron's The Hilltop is set in a West Bank settlement

Israeli fiction writers have set their narratives in rural kibbutzim, moshavim, in small mainly Sephardic towns, in urban settings in Israel’s three largest cities, as well as overseas, and now novelist Assaf Gavron has set his fifth novel and seventh book The Hilltop (published last week by New York publisher Scribner) in perhaps the most controversial setting of all, an unauthorized West Bank settlement. In my New York Journal of Books review I recommend The Hilltop “to all readers who enjoy a good story grounded in current events.”

British author William Sutcliffe also set his Young Adult novel The Wall in what appears to be a West Bank settlement, but his settlers are represented by a single abusive two dimensional character. By contrast, Gavron’s settlers in The Hilltop are more complicated and more believable characters.

Roughly one in twenty Jewish Israelis lives in a West Bank settlement. Four fifths of these settlers live in settlements close enough to Israel’s 1949 armistice line that they could be incorporated into Israel as part of land swaps in a comprehensive peace agreement.

Gavron’s settlers in the fictional settlement Ma’aleh Hermesh C are among the fifth of settlers who would have to be evacuated in the event of such a peace agreement, and since it is an unauthorized settlement, an order for its evacuation has already been issued. Whether that evacuation order will ever be executed is a central plot element in The Hilltop.

My recommendation “to all readers” in my NYJB review may be too broad. Perhaps the ideal reader is one who can care about the novel’s characters (even though they show no empathy toward their Palestinian neighbors) while at the same time disapprove of their settlement enterprise and its objectives, one of which is to prevent a comprehensive peace agreement to end the Israel-Palestine conflict through the partition of the country into two states, Israel and Palestine.

This past spring U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said, “A two-state solution will be clearly underscored as the only real alternative. Because a unitary state winds up either being an apartheid state with second-class citizens—or it ends up being a state that destroys the capacity of Israel to be a Jewish state.”

There are indeed Israelis who share Secretary Kerry’s apprehensions, but they include some of Israel’s newly affluent shoppers who consume organic produce and dairy products produced in settlements similar to Gavron’s fictional Ma’aleh Hermesh C. For a fuller discussion of The Hilltop see my NYJB review.

Israeli books: Assaf Gavron's The Hilltop is set in a West Bank settlement

Israeli fiction writers have set their narratives in rural kibbutzim, moshavim, in small mainly Sephardic towns, in urban settings in Israel’s three largest cities, as well as overseas, and now novelist Assaf Gavron has set his fifth novel and seventh book The Hilltop (published last week by New York publisher Scribner) in perhaps the most controversial setting of all, an unauthorized West Bank settlement. In my New York Journal of Books review I recommend The Hilltop “to all readers who enjoy a good story grounded in current events.”

British author William Sutcliffe also set his Young Adult novel The Wall in what appears to be a West Bank settlement, but his settlers are represented by a single abusive two dimensional character. By contrast, Gavron’s settlers in The Hilltop are more complicated and more believable characters.

Roughly one in twenty Jewish Israelis lives in a West Bank settlement. Four fifths of these settlers live in settlements close enough to Israel’s 1949 armistice line that they could be incorporated into Israel as part of land swaps in a comprehensive peace agreement.

Gavron’s settlers in the fictional settlement Ma’aleh Hermesh C are among the fifth of settlers who would have to be evacuated in the event of such a peace agreement, and since it is an unauthorized settlement, an order for its evacuation has already been issued. Whether that evacuation order will ever be executed is a central plot element in The Hilltop.

My recommendation “to all readers” in my NYJB review may be too broad. Perhaps the ideal reader is one who can care about the novel’s characters (even though they show no empathy toward their Palestinian neighbors) while at the same time disapprove of their settlement enterprise and its objectives, one of which is to prevent a comprehensive peace agreement to end the Israel-Palestine conflict through the partition of the country into two states, Israel and Palestine.

This past spring U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry said, “A two-state solution will be clearly underscored as the only real alternative. Because a unitary state winds up either being an apartheid state with second-class citizens—or it ends up being a state that destroys the capacity of Israel to be a Jewish state.”

There are indeed Israelis who share Secretary Kerry’s apprehensions, but they include some of Israel’s newly affluent shoppers who consume organic produce and dairy products produced in settlements similar to Gavron’s fictional Ma’aleh Hermesh C. For a fuller discussion of The Hilltop see my NYJB review.

Assaf Gavron

Assaf Gavron