"Anglophone readers (especially those who also read Hebrew) will find both this handsome book’s bilingual presentation of Ruebner’s selected poems, and his heart wrenching backstory described by translator Rachel Tzvia Back in her informative introduction and endnotes, compelling reading."

"Anglophone readers (especially those who also read Hebrew) will find both this handsome book’s bilingual presentation of Ruebner’s selected poems, and his heart wrenching backstory described by translator Rachel Tzvia Back in her informative introduction and endnotes, compelling reading."My two part review begins with the poet's bio and backstory in New York Journal of Books and continues with a discussion of his poems in an article that appeared in a different and now defunct publication, which begins with the next paragraph.

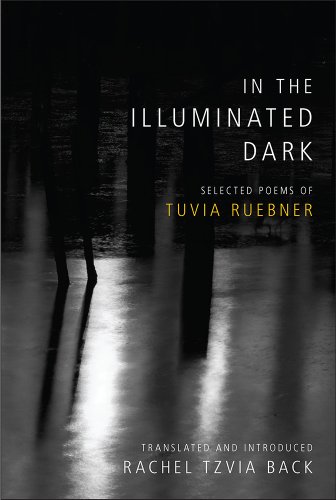

Israeli books: In the Illuminated Dark: Selected Poems of Tuvia Ruebner

Although Tuvia Ruebner is the author of 15 books of poetry in Hebrew and nine translated into German spanning six decades, twice winner of Israel’s Prime Minister’s Prize, 2008 winner of the Israel Prize, as well as Germany’s Konrad Adenauer Prize, only a handful of his poems were available in English in anthologies and literary magazines prior to the joint publication this spring by by Hebrew Union College Press and University of Pittssburgh Press of In The Illuminated Dark, a bilingual edition of his selected poems translated by Rachel Tzvia Back. I am grateful to Adam Kirsch's Tablet article on Ruebner which introduced me to this amazing poet.

In my New York Journal of Books review I write, “Anglophone readers (especially those who also read Hebrew) will find both this handsome book’s bilingual presentation of Ruebner’s selected poems, and his heart wrenching backstory described by translator Rachel Tzvia Back in her informative introduction and endnotes, compelling reading.” See that review for the backstory.

Suffice to say that the predominant theme in Ruebner’s poetry is loss; loss of parents, grandparents and a sister in the Shoah, of his first wife to a traffic accident, and of his youngest son Moran who cut off contact with his parents during a trip overseas. In the untitled poem that begins the section of the book entitled History Reubner lists all the relatives, friends and colleagues whom he has lost devoting one line to each person in the 30 line poem except for Moran who gets five lines. Ruebner also refers to Moran in the poems “1983” (1990), “Soldiers’ Memorial Day” and “Moonlit Night (2)” (2002), “Not Every Day” (2009), and “A Meeting in Venice,” “Avraham,” “Father,” and “He” (2013).

“Not Every Day” is an apology. When Moran returned from combat in Israel’s first Lebanon War he had changed, but his parents didn’t notice. Ruebner doesn’t specify how Moran had changed; perhaps he had PTSD. On his way to South America Moran stopped in Cambridge, MA where his father was spending a sabbatical at Harvard to bid his parents farewell. After a few letters all traces of him were lost. In “Not Every Day” Ruebner writes,

“I embraced you there when we parted at the winter airport,

a leave-taking seared into my flesh. You asked ‘why?’

for something foreign had wormed its way between us after that cursed war.

You returned to us different from what you had been before, but I was

tense, unable to concentrate, troubled by the sabbatical that had

come to nothing.

How sorry I am, how deeply repentant, for not understanding

what you went through without us, for responding severely.”

After telling Moran how much he misses him Ruebner concludes the poem, “Self pity is contemptible. But your love is eating me alive.”

It’s probably just a coincidence, but the venue and the line “something foreign had wormed its way between us” reminds me of a Turkish Jewish character in Mario Levi’s novel Istanbul Was a Fairy Tale who becomes a Mormon while studying at Harvard and writes to his family informing them that he intends to have no further contact with them. But in Reubner’s case it is the parent who is at Harvard and the adult child is only passing through en route to another destination, so the coincidence in all likelihood is only a superficial resemblance.

In “He” Ruebner writes about not being able to stop thinking about him (presumably Moran) and even wanting to kill him, which calls to mind the parents in David Grossman’s Falling Out of Time who are tormented by the memory of their deceased children. Writing is Ruebner’s only remedy: “Only when I write about him does he leave me be.”

Not all of Ruebner’s poems are that bleak. “What Joy” (2013) describes the joy Ruebner feels upon learning he has become a great-grandfather and ends with “…a great-grandfather embracing a great-grandmother/and kissing her on the mouth as though he were a boy of twenty.” “Chimes” (2009) playfully closes with a feminine rhyme of his wife’s name Galila and the Hebrew word for chimes mitsilah, which in turn resembles the Hebrew verb to save or rescue hitsil; perhaps he is crediting Galila with psychologically rescuing him.

Neither of Ruebner’s remaining children live in Israel. Miriam, his daughter from his first marriage married a man from Iceland and lives there with her children and grandchildren, and his son Idan is a Buddhist monk who lives in Nepal, but both are in frequent telephone contact with Ruebner. I wonder whether Reubner’s ambivalence about Israel, which he expresses in his protest poems, influenced his children’s decision to emigrate.

There is a saying among literary translators that literal word for word fidelity to a text betrays the text. In my NYJB review I praise Back’s translation of Ruebner’s poetry which she creatively does not betray. In “Poem” (2009), for example, Ruebner’s rhyming couplet in the fourth stanza does not rhyme in English, but in the fifth stanza Back adds a word not found in the Hebrew to achieve a slant rhyme. And while the first word of the second line of “The Tower of Babel (2)” (1999) means “blind” in both versions, in the Hebrew the adjective blind modifies a noun in the first line, while in Back’s English version it modifies a different noun in the second line.

Ruebner is an award winning translator between Hebrew and German (Agnon into German and Goethe into Hebrew) and in all likelihood appreciates both the difficulties his verse posed for Back and her workarounds. Next spring Late Beautya book of Ruebner’s recent poems translated by a different team of translators will be published by Zephyr Press, and it will be interesting to compare their versions with Back’s.

I urge readers who have at least intermediate proficiency in Hebrew to use a dictionary or dictionary app and read Ruebner in the original, and I likewise urge those readers who have only prayerbook Hebrew to read the poems out loud even without understanding what the words mean to get some sense of the music of Ruebner’s poetry.

Ruebner is also a gifted photographer, and his poetry is not only sonorous but also visual, especially his travel, nature, and ekphrastic poems. Let’s conclude with his “Untitled” (2013)

“Like leaves driven in wind.

Like tattered remnants of a scene.

Like a night’s sobbing.

Like the moon’s red blindness.

Like the abyss of four in the morning.

Not like.”

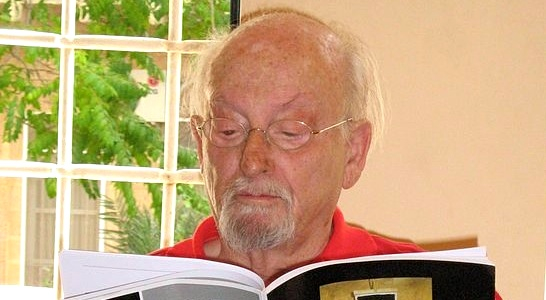

Tuvia Ruebner

Tuvia Ruebner