In my examiner article (next paragraph) I write:

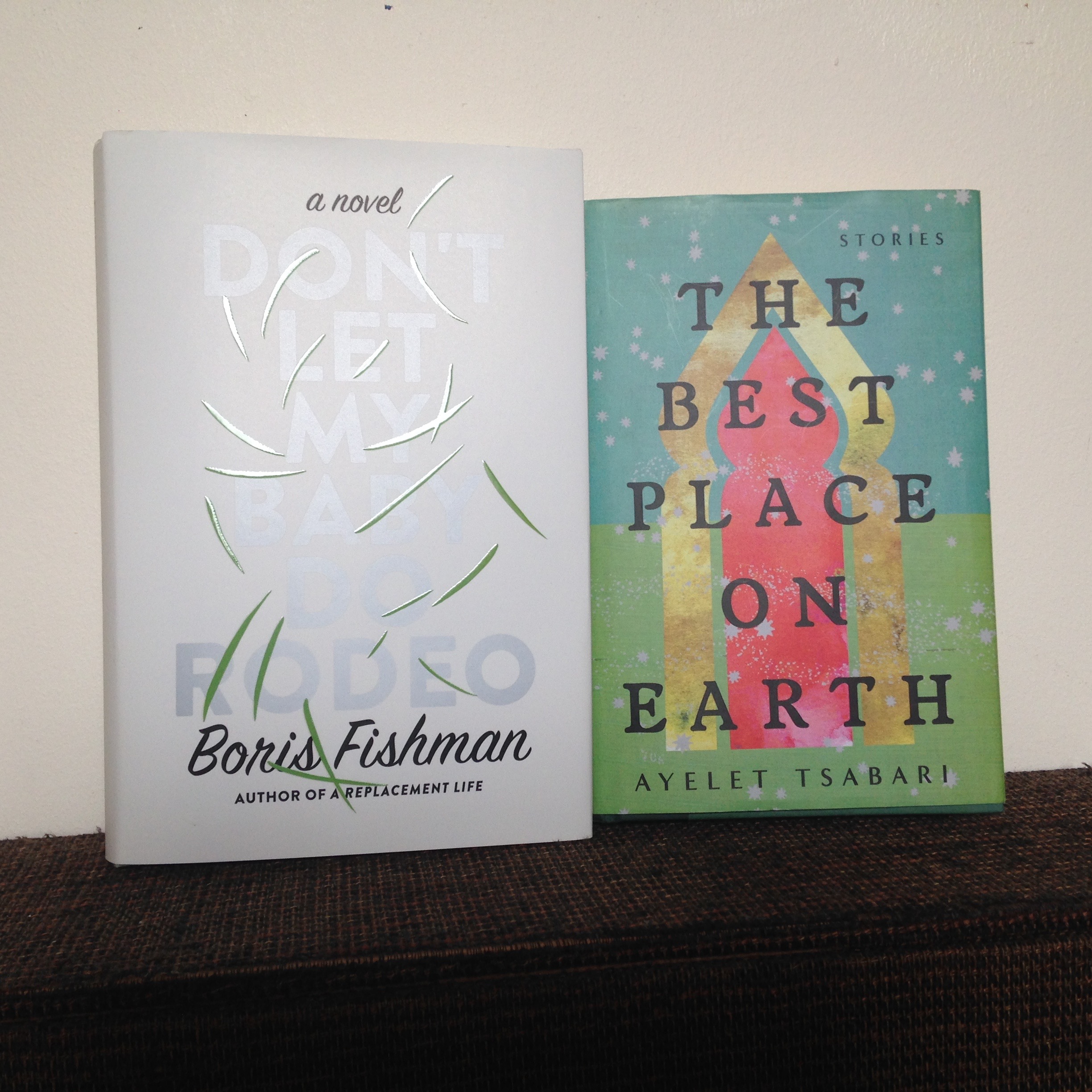

"Two fiction books published this month explore what home means for two distinct waves of recent immigrants. Boris Fishman continues to relate the experiences of Russian speaking Jews who immigrated to America in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s in his second novel Don't Let My Baby Do Rodeo, and Canadian-Israeli writer Ayelet Tsabari explores the lives of young Israelis at home and abroad in her debut book of short stories The Best Place on Earth: Stories, which won the Jewish Book Council’s $100, 000 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature in 2015 for the 2013 Canadian edition."

Also see my New York Journal of Books reviews of the two books:

In my examiner article (next paragraph) I write:

"Two fiction books published this month explore what home means for two distinct waves of recent immigrants. Boris Fishman continues to relate the experiences of Russian speaking Jews who immigrated to America in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s in his second novel Don't Let My Baby Do Rodeo, and Canadian-Israeli writer Ayelet Tsabari explores the lives of young Israelis at home and abroad in her debut book of short stories The Best Place on Earth: Stories, which won the Jewish Book Council’s $100, 000 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature in 2015 for the 2013 Canadian edition."

Also see my New York Journal of Books reviews of the two books:http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/book-review/dont-let-my-baby http://www.nyjournalofbooks.com/bo…/b...

Moving is one of life’s most traumatic experiences and all the more so when moving to another country and living in a new language. Two fiction books published this month explore what home means for two distinct waves of recent immigrants. Boris Fishman continues to relate the experiences of Russian speaking Jews who immigrated to America in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s in his second novel Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo , and Canadian-Israeli writer Ayelet Tsabari explores the lives of young Israelis at home and abroad in her debut book of short stories The Best Place on Earth , which won the Jewish Book Council’s $100, 000 Sami Rohr Prize for Jewish Literature in 2015 for the 2013 Canadian edition.

In my New York Journal of Books review of Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo I synopsize Alex and Maya Rubin’s experiences as adoptive parents and how Maya in the second half of the novel becomes a femme fatale, a role that is foreshadowed earlier in the novel when Alex compares her to Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina:

“Railroad mind”—that was Alex’s term for the hive of Maya’s brain. Railroads made him think of motion, steam, frantic activity. What he really meant was that she was like some Anna Karenina—superfluously melodramatic. And Maya understood what he really meant only because she had a railroad mind.”

The age at which one immigrates also influences one’s ability to adapt to a new country:

“Alex had been ten years younger than Maya’s eighteen when his family had come to America; the Rubins had come for good, whereas Maya had come on an exchange program in 1988, the first year such things were possible. After college, Maya was supposed to return to the USSR—a plan altered by her love affair with Alex and the end of the USSR. Alex had taken to America—he spoke with confidence about Wall Street, the structure of Congress, technology. Maya conceded his authority. Only once had she exclaimed that in twenty years he had almost never left New Jersey, so what did he know? Alex had looked at her as if at a child who doesn’t understand what it means to say things one will later regret, and retreated upstairs. He did not speak to her for three days, their sullen meals spent communicating through Max and his grandparents, and Maya never said that again.”

Tsabari’s Israeli ex-pats are only a few years older than Fishman’s Maya was when she moved to America, and yet for them it is more of a choice. In my New York Journal of Books review of The Best Place on Earth I note how well adapted Tsabari’s Israeli-Canadians are to life in Canada. But in an article in LitHub Tsabari relates how hard won is her ability to write in her second language:

“During those first few years in Canada, even speaking in English was a challenge. I was discouraged by my failure to convey complex thoughts, irritated by my inability to fight with my boyfriend in an eloquent way, embarrassed by my frequent misunderstandings and mispronunciations.”

At a certain point she lacked mastery in both Hebrew and English, a feeling I experienced after living in Israel for five years when I sensed I was forgetting English but still didn’t write well in Hebrew. “My Hebrew was becoming rusty from lack of use, while my English was still not good enough. My dream of writing—the only dream I had ever truly held on to—was slipping away from me.”

While supporting herself by waitressing and cleaning homes and apartment building lobbies, Tsabari forced herself to write in English. Eventually the effort paid off and mirrored her emotional state now that she lived in Canada: “ I was calmer, lighter, more confident, and my English writing was cleaner, more straightforward, less flowery.”

Some of Tsabari’s stories set in Israel capture the stress and tension of living in a country where there is a constant threat of violence, which explains why for Tsabari’s Israeli new Canadians life there feels comparatively calmer.

It is said of the Israeli poet Leah Goldberg that she thought in Russian and wrote in Hebrew, and likewise the quality of Tsabari’s writing in English improved when she allowed Hebrew to influence it:

“Once I let my English writing be inflected with my Hebrew, infused with my voice, my accent, my background, and with the multiplicities of identity—the passion and drama of the Middle East, the oral traditions of my Yemeni ancestors, the tension and urgency of Israel—a new writer emerged.

“… Writing in a language foreign to me and to the place I am depicting seems fitting for a book like mine, preoccupied with in-between-ness. It adds layers of displacement that echo the experience of my characters, travelers, migrants, expats and outsiders who are often at a crossroads, in between places, in between identities, in between languages.”

That experience of displacement is something Fishman and Tsabari’s characters have in common. I conclude my review of Don’t Let My Baby Do Rodeo by writing that it “fulfills and surpasses the promise of [his debut novel] A Replacement Life.” Likewise I write that readers of Tsabari’s The Best Place on Earth will look forward to her novel in progress “with avid anticipation.” For a fuller discussion of these books read my reviews in New York Journal of Books.

No comments:

Post a Comment