“. . . the novel’s epic sweep, engaging prose, suspenseful plot, sense of humor, and introduction to a fascinating subculture outweigh its flaws.” - from my New York Journal of Books review. For additional remarks also see my examiner article, which begins with the next paragraph.

“. . . the novel’s epic sweep, engaging prose, suspenseful plot, sense of humor, and introduction to a fascinating subculture outweigh its flaws.” - from my New York Journal of Books review. For additional remarks also see my examiner article, which begins with the next paragraph.Jewish books: Gina Nahai's multi-genre Iranian-Jewish-American epic 5th novel

Some of our finest contemporary North American writers under the age of 60 immigrated to this continent as children and occupy a cultural middle ground between their countries of origin and the United States and Canada. Most contemporary Jewish North American immigrant writers were born in the various republics of the former Soviet Union, but some also came from the middle east, most notably Iran. Members of both immigrant communities can be found on both the east and west coasts, but the Russians tend to live in the northeast corridor, while the largest Iranian-Jewish community is in Los Angeles.

Iranian-Jewish-American writer Gina Nahai’s fifth novel,The Luminous Heart of Jonah S. (published last month by Akashic Books), starts in Los Angeles but flashes back to Iran for the first third of the book, and then returns to Los Angeles while also mentioning Iranian Jewish communities in Long Island and Canada (without, however, mentioning Iranian Israelis who, though not fabulously wealthy, include a former president, cabinet ministers, and an IDF chief of staff). In my New York Journal of Books review I write, “the novel’s epic sweep, engaging prose, suspenseful plot, sense of humor, and introduction to a fascinating subculture outweigh its flaws.”

Before the Iranian revolution of 1979 upper middle class and wealthy Iranians were considered the most western-like middle easterners (though secular Turks might beg to differ), but in The Luminous Heart of Jonah S. we learn of such Iranian concepts as aabehroo, which “means making sure you do everything in compliance with society’s idea of what is right, that you live honorably and protect the sanctity of your family’s name and reputation.” Americans, by contrast, are far less conformist, and some of us are frankly shameless, though the same could be said of the novel’s Iranian-Jewish villain.

Nahai uses magical realism to represent middle eastern superstition and also reveals class and regional animosities within Iran’s Jewish community where wealthy and highly educated residents of Tehran viewed less affluent provincials with condescension. After fleeing revolutionary Iran with the clothes on their backs many of the upper class immigrants had to start over in this country from scratch. Some have subsequently risen to even greater heights while others have had to adjust to diminished circumstances.

The novel also presents the boundaries between pre-revolutionary Iran’s Jewish and Muslim communities as more porous than outsiders might have guessed. For a fuller discussion of The Luminous Heart of Jonah S. see my NYJB review.

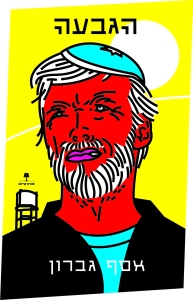

Assaf Gavron

Assaf Gavron